As part of the National Archives’ 20s people season, Alexandra Palace interpretation and curatorial manager, Kirsten Forrest, sheds light on what the Park and Palace looked like 100 years ago.

The 20sPeople season is a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

The First World War saw significant upheaval for many institutions at home – and Alexandra Palace was no exception. Having been requisitioned by the government, it was finally handed back in 1922 to resume functioning as a ‘a place of public resort and recreation’.

During lockdown in 2020, archive volunteers at the Palace were able to commit some of their precious time to piloting a transcription project focusing on digitised records from the 1920s. This work has enabled a deep dive into the world of our grandparents and great-grandparents – and also reveals some surprising synergies with current times.

Directly comparing the First World War and the pandemic would be overly simplistic. But recurring themes of re-purposing, repairing and reopening our spaces here at Ally Pally, for the benefit of everyone, are prominent – both now and 100 years ago.

The legacy of war

The period from 1915 to 1919 saw the venue – built in 1873 as the ‘People’s Palace’ and set within 196 acres of parkland – closed to the public and converted into an internment camp housing 3,000 ‘enemy aliens’. When first reopened, it was used by government officials processing repatriation documentation, and not for the public.

There were still some opportunities for post-war fun once the park reopened on 27 March 1920, with popular events such as a concert in May attended by over 3,000 people.

The people return to the ‘People’s Palace’

In February 1922, the keys of the Palace were handed back to the Trustees. This act signalled a return to the intended purpose of Alexandra Palace, resuming entertainment and recreation for the masses.

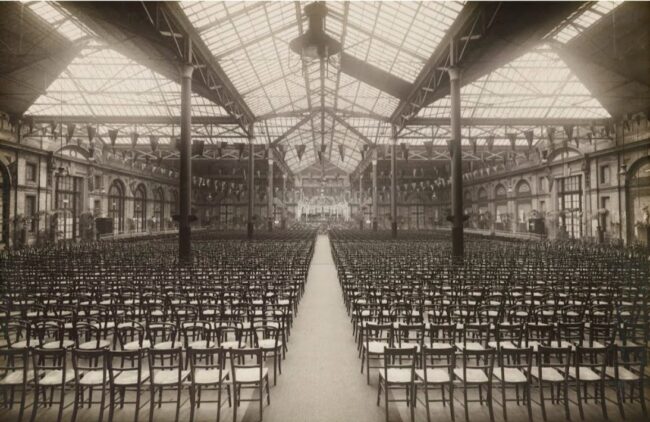

For the winter programme, the Industrial and Exhibition Hall (now the Ally Pally ice rink) was hastily converted into a concert hall.

The Christmas pantomime returned in the same year, complete with a forest scene featuring a waterfall and live deer, ponies, horses and hounds!

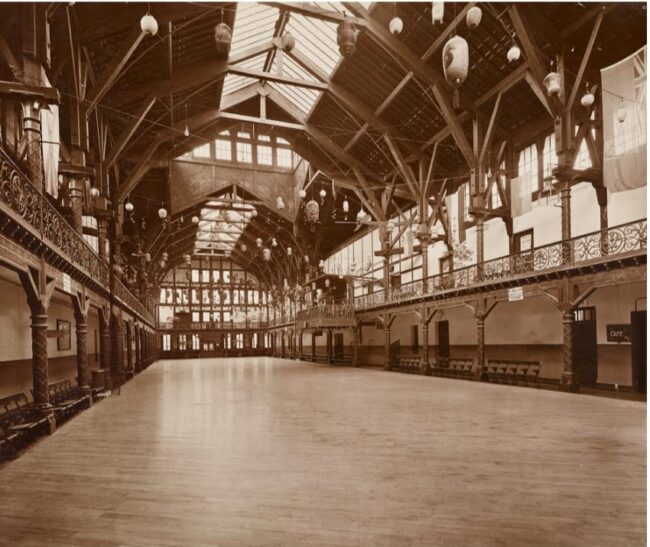

Meanwhile, the banqueting hall – built for refreshments, before the Palace itself – saw 1,300 dancers welcome in the new year of 1923. At 200 feet long and 60 feet wide, it was the largest dance hall in London.

The Palace’s popular clubs were also brought back into operation, offering badminton, indoor bowls and roller skating.

Significant challenges remained, however. The Palace’s Trustees expected similar treatment to the Crystal Palace, which was renovated and redecorated. However, the ‘tin gods in Whitehall’ seemed to have no interest in extending their support to north London. The Great Hall, with its leaky roof, rotten wooden flooring, and antiquated heating system, needed far more than the War Compensation Court offer of £11,000.

In the spirit of the venue, the trustees were adamant that ‘the show must go on’. Professional management was brought in for the first time in the history of Ally Pally when local resident W MacQueen Pope was appointed. He had an established career in the entertainment world and helped steer the organisation forwards. Well-known singers were attracted back to Alexandra Palace once again for concerts and performances.

The Theatre, which had been used as camp chapel and hospital during the First World War (see below), was refurbished and reopened, complete with the latest facilities, including electric lighting, heating and comfier seating! 1923 was the 50th anniversary of the opening of the first Alexandra Palace, and jubilee celebrations from 18-21 May are detailed in a souvenir programme from the archive which includes the following:

‘… It should be remembered that the Palace belongs to the Public … and that every penny spent therein goes to the improvement of the Public’s property. With adequate support the future of the Palace is assured.’

A sentiment which is echoed to this day.

The 1920s saw the Palace’s Amateur Dramatic & Operatic Society established, with Nancy Macmillan featuring as a star of the stage.

The August bank holiday crowds of 1923 sank 800 gallons of beer – almost as much as a darts’ world championship audience today! We seriously doubt they would match the consumption of a ton and a half of tea, plus 20,000 bottles of mineral water, though.

A programme for the Hornsey Conservative & Unionist Association Mammoth Fete in 1926, aside from exhorting readers to make sure they were registered to vote, also advertises a range of decidedly non-political entertainments including daylight fireworks, Punch & Judy shows, and a Palais de Danse (always sounds better in French!).

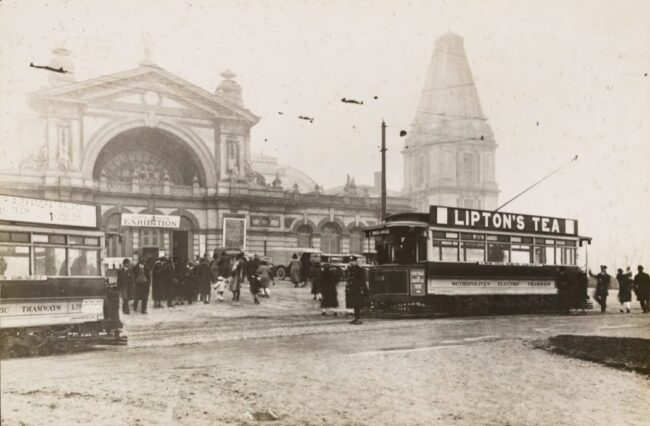

The North London Shows that brought the latest fashions and home improvements to post-war audiences proved highly successful, and of course the electric tram came right up the hill to the doors of the Palace.

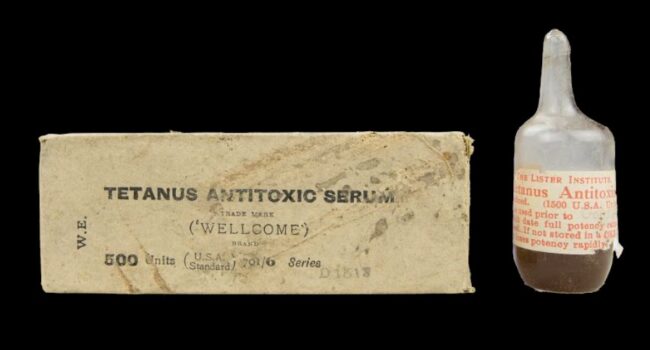

The Empire Exhibition programme of 1928 lists Trade Exhibitors’ stands as advertising pianos, fountain pens, boot polishes, Indian perfumes and various ‘domestic labour saving devices’. Some brands such as Cow & Gate are still household names. Hygiene was a concern 100 years ago (after the Spanish flu pandemic), as our archive reveals: ‘In the interests of public health, the premises will be disinfected daily with IZAL’. Parking was also becoming a concern, and fell under the ‘direct control’ of RAC attendants at a charge of two shillings and six pence.

In all, the 1920s were a period of recovery and rebirth that laid the foundation for significant advancements in the decades to come.

To modern times

It has been a pleasure to rediscover so many of these events from the 1920s through our archive. Comparisons between that era and now are undeniable. Over the last 18 months, the Palace has at times been forced to close, though in contrast to the war years the Park has remained open, welcoming five million people in 2020. The locked-down Palace was re-purposed for COVID testing centres and food distribution hubs, while charities used the empty kitchens to prepare food parcels for the most vulnerable in our community. Modern technology enabled streamed performances from the likes of Coldplay, Wolf Alice and Nick Cave to be hosted inside our walls. Meanwhile, we took our learning programme online to help home schooling, and organised socially distanced entertainment in local care homes.

With restrictions lifting, today’s Ally Pally team, like our counterparts in the 1920s, have welcomed audiences back for live music, theatre, comedy and major events, such as the darts, snooker and Earthshot Prize, which was held in that same theatre space where people were royally entertained a century ago.

During the pandemic we leaned on the spirit of endeavour and innovation that our predecessors had shown in rebuilding and re-awakening this iconic venue.

As a Charitable Trust we are so grateful for all the support from the public and local communities during the past year, as we continue to fulfil our public purposes to make the Park and Palace ‘available for the free use and recreation of the public forever’.