Researching and archiving – an overview from volunteer Keith Sagar

I knew of Alexandra Palace since I first came to London; the silhouette on the hill when the train was nearly at Kings Cross. Then, while I lived in grotty North London flats, a place for views over London, and the occasional rock concert (yes, back in the 1960’s). Then, becoming Muswell Hill residents, a family venue for fireworks, circus, boat shows, organ concerts, and a memorable school concert in the cold, damp abandoned, Old Theatre. I became an architect, and as understanding and re-using old buildings, rather than demolishing them, came into favour, I worked on some historic building projects, but I never managed to work on the Palace.

When I retired, I trained to get a tourist guide diploma, and also looked for local voluntary work. Visiting the Palace’s ‘War on the Home Front’ exhibition in 2014, I found there were opportunities at the Palace and Park, and I have been a volunteer at the Palace since 2015, mainly doing guided tours on our many routes. As my fellow volunteer guides have already written about this – or perhaps you have done one of our tours – I will instead say something about another volunteer activity – research and archiving.

There is a huge amount of information – facts, personal stories, collections of photographs documents, – about the Palace which constantly needs to be researched, recorded, put in order, and made available for many purposes – exhibitions, publications, website, displays.

Our tours are one example; we need accurate facts, stories, and memorable ‘take away points’ – something amazing, amusing, or previously unknown – to keep them fresh and interesting. These come from research and from the archives. On recent tours you could have been told about elephants, parachutists, alleged alien activities, the nuclear bunker, and much more; stories discovered, researched and recorded by our volunteer tour guides.

My own volunteer researching and archiving illustrates some of what can be done. I have followed the Palace’s suggestions, first from Curatorial and Interpretation Manager Kirsten, and more recently Archivist Melanie, about subjects for investigation.

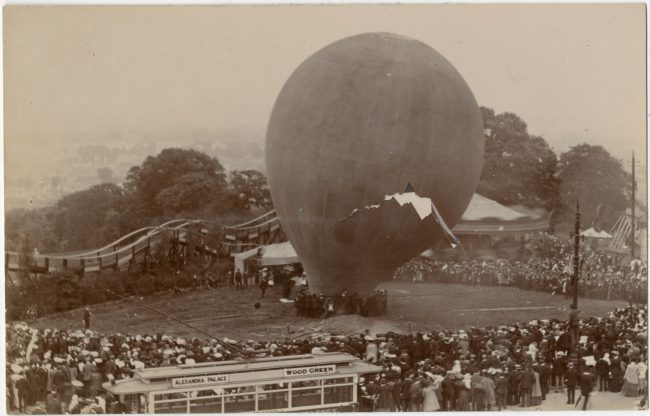

I started by looking at the Palace’s digital records – thousands of documents, images, drawings. They had a roller skating craze, outdoor events with person-carrying kites, and parachutists jumping from balloons, while the Great Hall had a cycle racing track for week-long events, massed choirs, and performances of the 1812 overture with full firework and cannon-fire effects (at least until the local residents objected ).

Then the Google Arts and Culture Project loaned the Palace a sophisticated digital scanner to record historical documents, many recently discovered in a locked cupboard, for the development of the Palace’s online archive. Over 8000 documents were scanned, and as volunteers we assisted with handling these. I particularly liked the unique documents about early television dating from 1936, when the BBC were literally inventing television broadcasting in the Alexandra Palace Studios in the 1930s; designers drawings and photographs of the studio sets, and scripts – typewritten carbon copies – many with the producer’s handwritten amendments in red crayon.

When contractors discovered some glass medical phials dated 1915, still containing liquid embedded in the theatre walls, I researched their background at the Wellcome Institute medical library. They were an early tetanus vaccine, which was produced for use by the Army in the First World War trenches. Presumably these vaccines were used in the makeshift hospital of the Palace internment camp for enemy aliens while it was requisitioned by the War Office from 1915-1919.

I also investigated the poet and painter Rudolf Sauter, born and educated in England but interned at the Palace during the wartime, presumably because of his German nationality. The Imperial War Museum Archive holds some of Sauter’s work, where I found poems, drawings, letters and a painting all depicting the Palace while it was an internment camp.

Striking and unusual – for the 1980s – artwork and wall paintings were a feature in some of the rooms rebuilt after the 1980 fire. There is a classical architectural theme, with enormous Greek-style gods, and ‘trompe l’oeil’ effects in which entire walls were painted with gardens, lakes and people to create the illusion of an outdoor space. The Royal Institute of British Architects library holds articles and information on the designers and artists involved, which I researched and recorded for use by the Palace. I am currently helping to investigate some of the documents – thousands of large architectural drawings stored in hundreds of rolls – from the 1980s rebuilding works. Among many frankly boring contractual documents are some high quality, sometimes unusual architectural design drawings (‘..based upon the Roman Parthenon…’ – that classical theme again!). Some drawings indicate still unrealised proposals such as a drama school, TV museum, hotel, while another – the observatory on top of one of the towers – has already gone, blown away by a gale.

It all reminds me how architecture used to be in the pre-digital age; this room full of documents could now be stored on one small hard drive and will very soon become part of our new digital database. The final satisfying result of all our investigative work and sorting through dusty boxes and files, will be to make the interesting drawings and information accessible to the wider public.