As part of our #BBC100 series of blogs exploring Alexandra Palace’s television heritage, we asked Open University historian Dr Daniel Weinbren to reflect on the context of British education broadcasts in the 1970s when the OU production centre was based at Alexandra Palace.

The BBC began making both formal and informal educational programmes for listeners and viewers from the 1920s. These included radio discussion programmes such as ‘The Fifty-One Society’ broadcast from 1951 to 1962, which included many adult education tutors among the contributors. The Midlands Region of the BBC broadcast six weeks of programmes based on the CCE O-level syllabus and this was followed by a national course called After School English.

There were also BBC schools broadcasts which spread to television in 1957. However, the dominant theory in the 1970s was that centralised lectures were not as effective as a child-centred pedagogy focused on activity and experience. It was argued that children learnt actively through interaction with the world, not passively from texts or adult authorities. Inspectors and teacher trainers tended to pay little attention to broadcasts, which were marginalised in report and analysis, as being passive transmissions, not supporting active learning. Nevertheless, BBC material was popular with teachers. Many schools programmes had associated publications for teachers and often also ones for learners. In the academic year 1965/66, 12.84 million BBC school publications were sold. In 1971 32,000 UK schools (ie over 90%) used more than 130 different BBC series. By 1979/80 BBC school publication sales had fallen to 5.96 million and the variety of programmes had also gone down, with 679 programmes in 1972/73, but only 356 by 1979/80, making up 409 hours of television. In that last year 96% of primary schools had TVs, with an average of 1.9 per school. However, although by 1976 colour televisions outnumbered mono sets in the UK, in schools fewer than half were colour TVs. During the subsequent decades BBC School Broadcasting declined. Some of the outputs appeared tangential to the new national curriculum, and there was competition from the private sector as other delivery platforms developed.

While the OU’s programmes were written by teams of academics and producers and funded by the OU, schools programmes were funded and produced by the BBC, guided by the BBC’s School Broadcasting Council (SBC). The SBC had connections to government and the OU. Dubious about some of the values and ideas of producers, in 1971 Secretary of State for Education Margaret Thatcher placed film director Bryan Forbes on the SBC. John Scupham, the first Controller of Educational Broadcasting, and a former SBC education officer, left the BBC in 1965 and worked closely with Jennie Lee on the creation of the Open University. He sat on Lee’s ministerial committee to advise on the Open University, then on its planning committee and finally on its first council. Professor of Social Psychology Hilde Himmelweit who had studied the impact of television on children, sat on these latter two bodies, and although not formally on the SBC, linked ideas about adult and children’s education.

The 1970s also saw the rise of educational broadcasts linked with the Open University. The OU opened to students in January 1971 and broadcast 124 programmes in its first year. As students progressed, more courses were written but the need for the original programmes remained and the number of programmes increased so that within a few years there were over 1,000 hours of OU BBC television and radio broadcasts. By 1978 there were 1,500 radio programmes, equal to about 26 hours of broadcasting a week, plus 300 new television and 300 new radio programmes that year. In 1979 the BBC transmitted 1,502 OU programmes over 35 hours a week, at a cost of £7,017 million. Growth could not be sustained and there was a severe reduction in OU programmes in 1983. This echoed a wider trend of falling interest in educational television around the world. Poor time slots, few repeats, uneven reception in some areas, academic distrust of non-print media meant that often broadcast material was not assessed and the percentage of students listening to or viewing OU programmes fell. To the relief of many producers and presenters the number of live programmes was reduced. Recordings were made available in study centres and summer schools (where OU students could meet tutors and fellow students face-to-face) and the OU started to loan playback equipment. TV still accounted for 20% of the OU’s teaching budget. Courses could only afford to make two programmes each – one of those would be simply talking heads, and in 1976 courses in geometry and philosophy, did not use any television with no apparent detrimental outcomes.

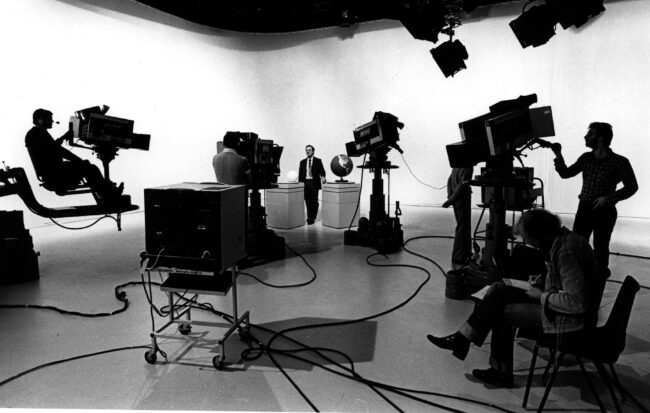

An agreement made with the OU in 1971 gave BBC the right to ‘refuse to transmit any programme or part of a programme which in the opinion of the Corporation contains anything defamatory or likely to bring the Corporation into disrepute’. Other disputes between the BBC and the OU included the timings of broadcasts, and even what was appropriate clothing for presenters. Nevertheless there was also co-operation. In 1973 the first of the OU’s degree awarding ceremonies was broadcast live from Alexandra Palace Great Hall. In 1977 the BBC presented a shortened version of Macbeth with printed notes provided to OU students. Filmed in Studio A at Alexandra Palace on a simple set, often a black background, the media was imaginatively employed, such as when Shakespeare’s three witches gathered around a cauldron and close-up images were overlaid on the bubbling liquid. Evolving approaches to production can be traced through from the first OU Foundation Arts broadcast in 1971 when three male academics discussed a 17th century poem on screen. For the replacement made in 1987 there was no presenter, but instead questions posed through captions. The third iteration featured poets reading poetry and talking about their responses to it. As the OU grew in confidence and expertise, the lecture format seemed an increasingly redundant teaching model, and the skills of BBC colleagues came to the fore.

(OU graduation ceremony in the Palace’s Great Hall)

Open University broadcasts provide evidence that teaching need not be the presentation of ideas by lone intellectuals. They demonstrate the crossover of notions of performance and production between schools and higher education and the benefits of collaboration whereby the form bolsters the content, which in turn informs the structure of the material.

Dr Daniel Weinbren, Curriculum Manager, The Open University

Daniel Weinbren wrote The Open University. A history, MUP 2014.

“The Open University’s unique partnership with the BBC continues to grow from strength to strength and has evolved to co-produce content across television, audio and digital channels and platforms. As part of the OU’s social mission we work with the BBC to create inspirational programmes to reach and engage audiences and inspire them to find out more about an exciting range of subjects and topics. You can find out more about our partnership at OU Connect”

Caroline Ogilvie, Head of Broadcast and Partnerships, The Open University