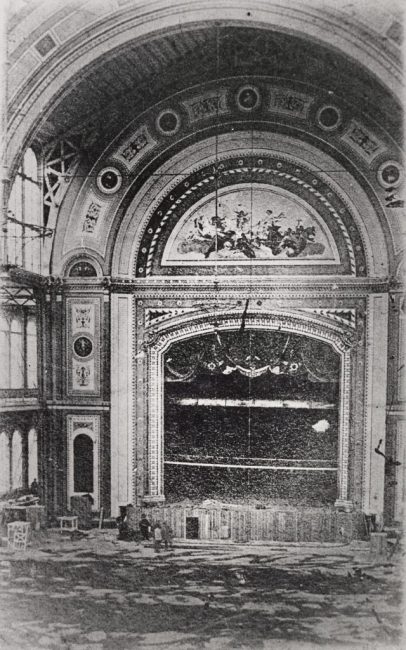

On 9th June 1873 fire struck the newly opened Alexandra Palace and destroyed the building and its grand Theatre. A re-designed second Alexandra Palace opened two years later in 1875 with a new Theatre as one of many cultural facilities. The first had been designed by architects Alfred Meeson and John Johnson, with the new, larger Alexandra Palace designed by Johnson alone.

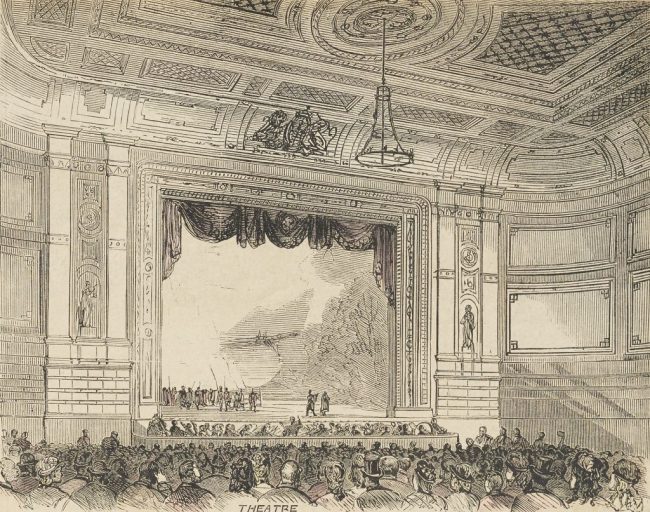

When it first opened it was designed to seat 3,000 people. However, the architect had little experience of theatre design, consequently, the large auditorium more closely resembled an oversized music hall or concert room. More successful for music than stage shows the auditorium had poor sightlines and the two shallow balconies at the rear were too far from the stage – an issue finally rectified in the newly restored Theatre.

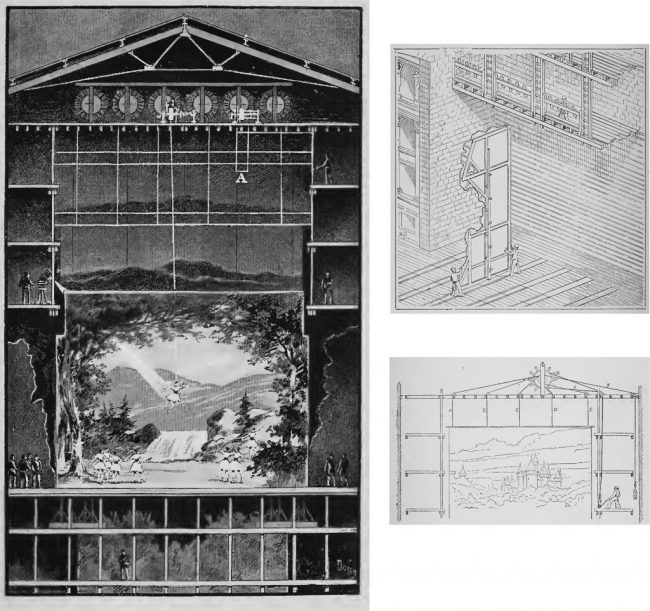

The architect had also made no provision for getting scenery on and off stage. To compensate for the idiosyncratic design of the Theatre, stage designers T. Walford Grieve and Sons had to ingeniously adapt the stage to make it fit for purpose. It is probably one of the earliest examples in English theatre architecture which had the facility for counterweight flying and is the last surviving of its kind in its original state. An innovative lock iron system prevented the heavy set pieces from crashing down on the stage hands below. To truly understand the complexity of the design and how the machinery might have worked, we are working with Lincoln Conservation to create a 3D scan to help us unlock its secrets.

When the theatre opened, it was a place of spectacle and delight with the stage machinery enabling performers to appear, disappear and be propelled through the air. In its heyday, the Theatre entertained thousands with pantomime, opera, dance, ballet, music hall and cinema.

The first productions made full use of the Theatre’s technology and size demonstrating its visual effects in the opening show Minerva. The Goddess Minerva descends from the heavens to create the arts and sciences, creating ‘the transition from barbarism to civilisation’ on stage, reflecting the lofty ambitions of the Palace’s creators. Beyond the sets and machinery a large cast and crew were required to achieve the spectacle, with the ballet featuring 150 dancers.

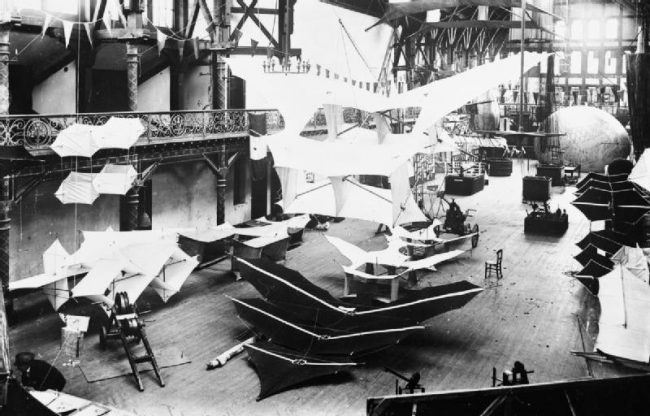

Pantomimes were a popular draw at the Theatre and showcased the novelty of stage tricks. The theatre’s first pantomime, The Yellow Dwarf, was packed with special effects such as actors disappearing through floors and magical transformations. A 1903 production of Aladdin saw actors fly across the stage with the use of Cody kites in place of a magic carpet. The kites were developed by the Wild West Showman, and pioneer of early manned flight, Samuel Franklin Cody who also performed at the Palace. An early example of ingenious product placement, the kites were demonstrated and experimented in the Park. The venue’s Blandford Hall was filled with Cody’s kites and other daring aeronautical equipment.

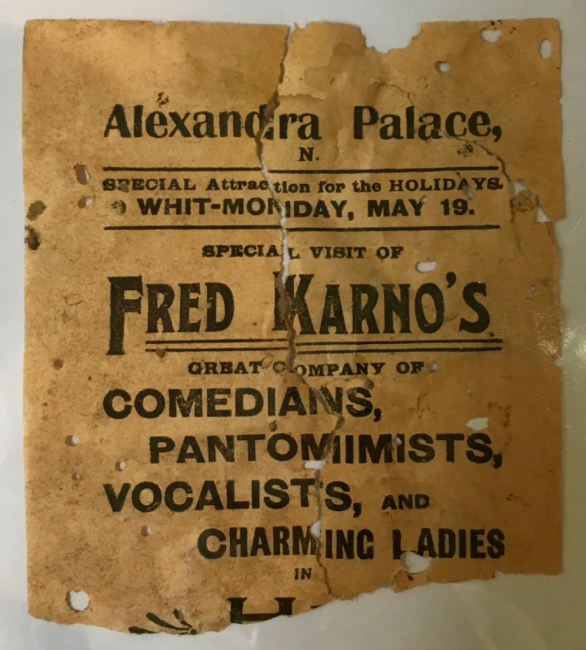

The Theatre hosted a variety of productions, with many travelling groups passing through. Fred Karno and his company performed at the Theatre in 1902. Manager Karno was notable having given starts to luminaries like Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel and Max Miller. Discovered during construction work on the Theatre balcony a scrap of flyer promoted his show His Majesty’s Guests. A contemporary review from The Era stated that the company received “roars of laughter by a crowded audience.”

When it opened, the Theatre rivalled that of many in the West End with its size and ambition, welcoming stars like Dame Ellen Terry and Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree. A grand start for the Alexandra Palace Theatre which would go on to become a home for both high-art and mass entertainment.

Be part of the biggest change at Alexandra Palace for a generation. All donations of £25 or more will be credited on our Donor Board, which will be installed in the restored East Court when it re-opens in December 2018. There is still time to name a seat in the Theatre too. Find out more here.